Don't Know

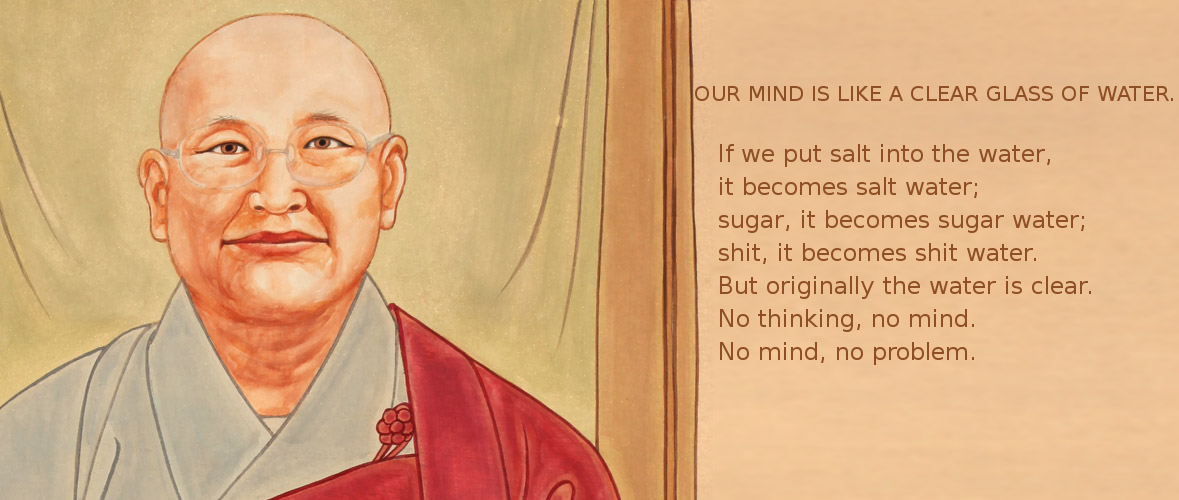

Zen Master Seung Sahn. Art from the website prajna-galleries

Zen Master Seung Sahn. Art from the website prajna-galleries

As many of you know we have been searching for a space to hold our meditation sessions and other events. We sent out a number of emails to area churches and looked at commercial office space to rent. A few times it looked like we found what we were looking for, only to discover some wrinkle that made the space either far less than ideal or unavailable. Last night I heard of the possibility of a fantastic space–better than any we have looked at so far. So the possibility of having a great meditation space may be on the horizon–or maybe not. This morning, while walking my dogs, I realized that this process of looking for a space is similar to the famous Chinese farmer story. For those unfamiliar with it it goes something like this.

Once upon a time there was a Chinese farmer who lost a horse–it ran away. And his neighbors came around that evening and said “That’s too bad! That is most unfortunate!” And he said “maybe.” The next day the horse came back and brought seven wild horses with him. And his neighbors came around that evening and said “Why that is fantastic, isn’t it?” And he said “maybe.” The next day his son was trying to train the wild horses and broke his leg while attempted to ride one. And, of course, the neighbors came around and said “That is awful! That’s too bad!” And the farmer said “maybe.” The following day army officers came around the village conscripting all young men into the military. They rejected the son because of this broken leg. Yet again, the neighbors came around and this time they said “Fantastic news, you must be very happy.” And the farmer said “maybe.”

So is it good news that we found a potentially wonderful meditation space? Maybe

Alan Watts said of the Chinese farmer story:

The This is from his book Eastern Wisdom, Modern Life: Collected Talks 1960-1969 (public library)whole process of nature is an integrated process of immense complexity, and it’s really impossible to tell whether anything that happens in it is good or bad—because you never know what will be the consequence of the misfortune; or, you never know what will be the consequences of good fortune.

I am at a truck stop in west Texas. Someone approaches me as I pump gas, tells me he has no money but he needs to get to Arkansas to stay with his brother. I give him $10. Will the consequences of that act be good or bad? I simply don’t know. Maybe good; maybe bad. We can extend this don’t know mind to everything.

Stephen Batchelor writes Confession of a Buddhist Atheist (public library)of his time in a Zen Monastery in South Korea:

All I do, hour after hour, is ask myself the question What is this? … All I did for ten hours a day for the next three months was ask myself this question. The first two weeks, when my back hurt and my mind swung between febrile daydreamsfebrile daydreams = fever-like daydreams and lethargy, and the last few days, when I strove unsuccessfully not to look forward to the retreat ending, were the hardest. Throughout the long middle period, I experienced an unprecedented contentment.

The point of this exercise, common in Zen, is to

short-circuit the brain’s answer-giving habit and leave you in a state of serene puzzlement. This doubt, or “perplexity” as I preferred to call it, then slowly starts to infuse one’s consciousness as a whole. Rather than struggling with the words of the question, one settles into a mood of quiet focused astonishment, in which one one simply waits and listens in the pregnant silence that follows the fading of words

Zen Master Seung Sahn wrote in a letterThis is from his wonderful book Dropping Ashes on the Buddha: The Teachings of Zen Master Seung Sahn (public library):

You must keep don’t know mind always and everywhere. This is the true practice of Zen.

The Great Way is not difficult

if you don’t make distinctions.

Only throw away likes and dislikes

and everything will be perfectly clear.

So throw away all opinions, all likes and dislikes, and only keep the mind that doesn’t know. This is very important. Don’t know mind is the mind that cuts off all thinking. When all thinking has been cut off, you become empty mind. This is before thinking. Your before thinking mind, my before thinking mind, all people’s before thinking minds are the same. This is your substance. Your substance, my substance, and the substance of the whole universe become one. So the tree, the mountain, the cloud and you become one. Then I ask you: Are the mountain and you the same or different?

The mind that becomes one with the universe is before thinking.