Wild, Wild Country

I am using this copyrighted opening graphic image under Fair Use to identify the documentary. The copyright is believed to belong to Netflix.

I am using this copyrighted opening graphic image under Fair Use to identify the documentary. The copyright is believed to belong to Netflix.

My wife, Cheryl and I have been watching the Netflix documentary series Wild, Wild, Country. It’s about the Indian Guru Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh (Osho), his assistant Ma Anand Sheela, and the community they formed in Oregon, Rajneeshpuram in the 1980s. I highly recommend this documentary and I am not alone – on Rotten Tomatoes it earned a 98% tomato rating. That’s not to say the documentary is perfect. It doesn’t address the teachings of the Bhagwan nor what his followers, the sannyasins believed. It focuses more on the cascade of bad things rather than the positive. And to accentuate that, we get a tense, ominous soundtrack.

This is a complex story. Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh had some good ideas and good intentions. I think the Oregon Rajneeshpuram was filled with compassionate people who were trying to live a good life. People from all walks of life left those lives to live on a commune in a desolate region of Oregon. I believe they did this to create a better life for themselves and build a better society. People from the local town of Antelope were also compassionate people who cared for their families and people in their town. But ego got in the way. The sannyasins felt they were better than the locals who in their minds were hicks. And the locals got more and more concerned as the population of Rashneeshpuram expanded into the thousands. People on both sides were getting more and more bizarre, bombs exploding, bioterrorism. Eeeks! Watching this, in the comfort of my living room, 35 years after the fact, I can see that there were many opportunities to defuse the situation, and for the local community and Rashneeshpuram to live in harmony. It is easy to see how misguided they were. And here is where my ego enters the picture. I think Those people are misguided and I would not be. I, sitting here in my living room, perpetuate the problem. You see, those people are misguided I would not be is a me vs. them thought and antithetical to buddhism. And with a little reflection I see that I share the feelings and emotions those townspeople and sannyasins felt. The sannyasins felt they were better than the townspeople and I have had feelings of being better too – and those feelings still arise. The townspeople had some fear of people different from them, and I have those fears too. We all have the potential for explosive conflict. Our path is to recognize feelings such as fear and anger as they arise in us, refuse to react out of them and respond in an enlightened way.

Cajon and Practice - Part 2

I started playing music when I was eight–my parents thought it would be a good idea for me to learn to play accordian. So I took lessons with my uncle, a professional accordian player in Milwaukee. My older brother had been taking according lessons from him for years and in my mind my brother was what an accordian student should sound like. But when my eight year old self tried to play, I didn’t sound as good as my brother. I wanted to sound good, but I didn’t and accordian playing ended up being a completely frustrating experience. I abandoned the accordion as quickly as I could. A year or so later I switched to another instrument. In high school I was one of the best musicians. I had great fun playing; it was relaxing not stressful; and I didn’t need to practice much. As a senior I won both music awards my high school offered. I was Mr. Hot Stuff music-wise in my tiny corner of the universe: Boys’ Tech and Trade High School in Milwaukee.

As a freshman in college majoring in music I discovered that I wasn’t so hot. There were tons of people better than me. Some phenomenally better. I thought I sucked compared to them. And as a result of this thought, I had fears before and during performing because I thought I would screw up in front of people. And because of these stresses and fears I did screw up which just confirmed those fears. I was a performance anxiety wreck. Over the next few years these fears greatly diminished. I can’t explain why that was. Maybe it was the camaraderie in the suite of practice rooms–the feeling that we were all in this together. The silly imprompteu late night jams. Finally I could once again play music for the sheer joy of it. I could feel the ecstasy in the music and feel connected to the other musicians in the band.

Years later, as an adult, I became a student in the piano studio at New Mexico State University. This required something new: playing alone on stage. And playing complex compositions from memory. Those dormant fears returned. I felt I sucked compared to the other students and I had fears of screwing up. In reflecting on that year, I can say that fear and anxiety are not good for memory. Let’s say my playing wasn’t effortless.

Kenny Werner in his book, Effortless Mastery (public library)“Effortless Mastery: Liberating the Master Musician Within” says “When you approach your instrument, no matter what lofty goals you say your have, wanting to sound good will predominate and render you impotent.” He mentions

For example, some horn players I’ve worked with didn’t have a rich tone. In working with them, I’ve often found that they weren’t really taking a deep breath and moving it through their horn. Doesn’t it seem odd that horn players wouldn’t take a deep breath? Why is that? Because they are afraid to commit themselves to what’s going to come out. A really deep breath is going to add tone and weight to the next phrase, but the horn player is not sure about the next phrase. His lack of confidence causes a shorter breath, and a shorter breath creates a weaker tone… The result confirms the player’s fears.

Fear takes away the strength of what you are doing. Without fear of wrong notes, you would feel the body’s craving for more air, and a new posture would emerge spontaneously. [Pianists] don’t let their arms move freely because they are afraid to play poorly. The result is anemic tone and rhythm. In this way their fears are confirmed.

A self reinforcing loop: I have a fear of playing bad. That fear and anxiety makes me play bad, which in turn reinforces my fear.

Werner then quotes from the book Zen and the Art of Archery Zen in the Art of Archery by Eugen Herrigel (public library) about shooting an arrow: > The right short at the right moment does not come, because you do not let go of yourself. You do not wait for fulfillment, but brace yourself for failure.

He adds:

There’s nothing wrong with wanting to play well, but needing to play very well is the problem.

The path out of this pit is to work on accepting who you are right now and–I am hoping this next bit makes sense–to have a plan rather than a goal. Shunryu Suzuki, a famous Zen Roshi has a nice quote:

Each of you is perfect the way you are… and you can use a little improvement.

There is a prayer that we recite at Zen services that ends

I now wholeheartedly accept who I am

Kenny Werner writes:

My four-year-old daughter can walk over to the piano and enjoy herself more than ninety-five percent of the professional pianists.

What does this have to do with Zen?

We face similar obstacles when we sit in meditation. We try to be 100% present in the moment and “just sit.” We have some idea of what a perfect meditation would be. But we end up having all sorts of thoughts in our heads. Or we might think “this meditation is not as good as the one I had last week.” Or going beyond the meditation cushion, we might have a goal of being a good person and leading a good life (however we define ‘good’), but we constantly fall short. It is frustrating both on and off the cushion. Before we even start the meditation session we might fear we are going to screw it up.

Returning to playing an instrument,

And perhaps that same four-year-old daughter can sit on the floor with the dog and be present in the moment better than ninety-five percent of Zen students.

Throughout the day a little voice in our head critiques your performance. I’m not good enough. I should concentrate on the moment more. I should meditate longer. I should have been kinder to that woman on the phone.

Hope

Photograph of Rebecca Solnit by Sallie Dean Shatz.

Photograph of Rebecca Solnit by Sallie Dean Shatz.

This is an extraordinary time full of vital, transformative movements that could not be foreseen. These quotes are from the book Hope in the Dark: Untold Histories, Wild Possibilities (public library) by Rebecca Solnit It is also a nightmarish time. Full engagement requires the ability to perceive both. The twenty-first century has seen the rise of hideous economic inequality, perhaps due to amnesia both of the working people who countenance declines in wages, working conditions, and social services, and the elites who forgot that they conceded to some of these things in the hope of avoiding revolution. Worse […] is the arrival of climate change, faster harder, and more devastating than scientists anticipated.

There are times when it seems as though not only the future but the present is dark: few recognize what a radically transformed world we live in, one that has been transformed not only by such nightmares as global warming and global capital, but by dreams of freedom and of justice — and transformed by things we could not have dreamed of… We need to hope for the realization of our own dreams, but also to recognize a world that will remain wilder than our imaginations.

The evidence is all around us of tremendous suffering and tremendous destruction.

Hope doesn’t mean denying these realities. It means facing them and addressing them by remembering what else the twenty-first century has brought, including the movements, heroes, and shifts in consciousness that address these things now.

It is important to say what hope is not: it is not the belief that everything was, is, or will be fine. The evidence is all around us of tremendous suffering and tremendous destruction. The hope I’m interested in is about broad perspectives with specific possibilities, ones that invite or demand that we act.

Alan Watts reading the Story of the Farmer

Zen Service

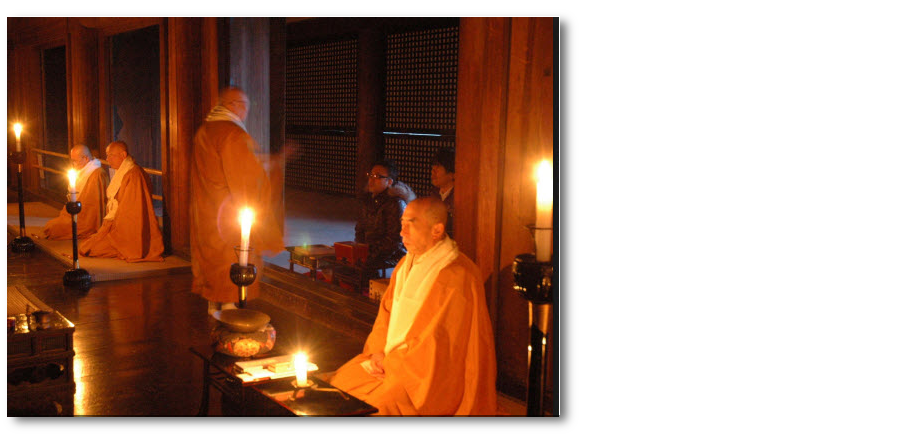

Image from What’s the Deal with Zen Ceremonies blog post by Brad Warner

Image from What’s the Deal with Zen Ceremonies blog post by Brad Warner

I am happy to announce that we will be having a3rd floor, Suite 331, 217 Princess Anne Street, Fredericksburg, VA across from Carl’s Ice Cream. There is an elevator. formal Zen service on Sunday, September 11th at 2pm at our George Washington Executive Center location. This is an auspicious time because it comes at the time of a major Buddhist holiday in Japan, Ohigan (到彼岸).

This Zen service will be an annotated one meaning that I will pause the service at a number of points to explain the significance of what we are doing. It consists of chanting both in English and Sino-Japanese, zazen (seated meditation), tea and a dharma talk. It should last a little over an hour.

Introduction to Zen Buddhism (public library)

If you read any of the popular books about Zen you may be surprised that Zen has any formal ceremonies. For example, a classic book on Zen, Introduction to Zen Buddhism by D. T. Suzuki says:

Zen … is not a religion in the sense that the term is popularly understood; for Zen has no God to worship, no ceremonial rites to observe, … Zen is free from all these dogmatic and ‘religious’ encumbrances.

Zen is viewed as one of the most austere forms of from The Teacup and the Skullcup: Chögyam Trungpa on Zen and Tantra (public library)Buddhism devoid of ceremony. Chögyam Trungpa Rinpohe writes:

[Zen] is the accuracy of black and white. In the Zen tradition there is no gray, nor is there yellow, red, green, or blue: it is black and white. That is the paramita of meditation: dhyana practice, Zen practice, Ch’an. Dhyana, Zen, and Ch’an all mean meditation.

But Zen has plenty of ritual and ceremony. However, there is a What’s the Deal with Zen Ceremonies blog post by Brad Warnerdifference between a Zen ceremony and one from another faith. Brad Warner writes:

Although the ceremonies at Zen temples might look like the ones you see at houses of worship in other faiths, the approach we take is a little different. No one ever insists you must believe in any of the rituals and chants and suchlike in Zen. You’re not worshipping anyone. You’re not pledging your allegiance to the temple or to Buddha. You’re not heaping praise upon unseen entities.

The chanting is just chanting. The bowing is just bowing. The bells are just bells.The statues are just statues. The priests are just people. The combined activities engaged in at these ceremonies have a genuine effect that you can feel. But there is nothing supernatural about any of it.

There is a story that Peter Levitt, poet and Zen priest tells. Peter Levett is a beat poet and he tells the story of going to a 7 day meditation retreat lead by the Dalai Lama (the Dalai Lama was 27 at the time). So it was Peter and a bunch of other poets including Alan Ginsberg. One day of the retreat The Dalai Lama was teaching them to chant in Tibet with various hand motions. One of the poets goes up to Peter and says “go over to Alan and listen to him chant.”” So he goes up to Alan, and hears him intoning “Eenie Meenie Miny moe…” And Peter says “Alan, what are you doing?” To which Alan replies “Hey, it works”.

subscribe via RSS