Cajon and Practice - Part 1

For my birthday my wife bought me a cajon (a wooden box drum). (Set aside for a moment your cognitive dissonance of the thought of a 64 yr. old Zen Buddhist Monk playing something as cool as a cajon.) Here is my current plan on learning to play.

The Plan

I am not even going to open the box until I can play the cajon. Here’s the plan. Every Sunday I am going to watch YouTube cajon videos (like the one above and this one and this one). So I will do that for at least 2 hours every Sunday. And I bought a bunch of books from Amazon about playing the cajon. Here is an excerpt from one:

I am not even going to open the box until I can play the cajon. Here’s the plan. Every Sunday I am going to watch YouTube cajon videos (like the one above and this one and this one). So I will do that for at least 2 hours every Sunday. And I bought a bunch of books from Amazon about playing the cajon. Here is an excerpt from one:

There is no question about this relationship of the top arm to the level where tone is produced. If the fingers, hand, or forearm have any bearing down on their own initiative, the tone simply does not come off. They each become an integrated unit with the top arm control; they make the top arm effective in contacting tone.

I am not entirely sure what that means but it sounds important. So I will memorize it. I am going to dedicate 1 hour a day to reading these books and memorizing the material in them. So that is my plan. It is the start of June now and if I do this to mid-August that will be about 100 hours devoted to learning to play the cajon. Then I will take the cajon out of the box, unwrap it, sit down and play the cajon flawlessly.

How’s that for a plan?

Maybe you are thinking that I won’t successfully play the cajon and I bet it is that you think I am not spending enough time on my new hobby. So here is my new plan.

The Revised Plan

Basically it is the same as the first except I will spend 20 hours per week watching YouTube videos and reading books and I will not open the box until Christmas. That is 1,000 hours devoted to learning to play the cajon–10 times more than the previous plan. Won’t it be a lovely gift to my wife to wake up on Christmas morning to some virtuosic cajon beats.

I think everyone can see that this plan is totally misguided. What is missing is practice, and plenty of it. If I did deliberative practice for those 20 hours per week instead of reading and watching YouTube videos, I probably could lay down some dope beats by Christmas. In the musical realm it is quite obvious to all of us that practice is the key.

But what about our spiritual life? This blog post is nearly identical to a talk I gave years ago about this topic. Here is the YouTube link. What people view as a foolhearty plan related to the cajon, they may view as valid when related to a spiritual path. Going to Sunday service, watching inspirational YouTube videos, reading books. That sounds good. But if that is the extent of it, it is as misguided as my cajon plan. What is missing is practice and plenty of it. You may think I DO practice. I read something in a book and apply it to my everyday life. That may work for some things, but I think it is equivalent to me buying a cajon and immediately joining Santana. I will read books at night and apply what I learn to me playing on stage with Santana. But clearly, a Santana stage performance is too complex to just jump into and apply what I learned watching YouTube videos. All the band members of Santana have spent years learning to play their instruments. And the band itself practices for hours. Hiromi, a phenomenal jazz pianist says this about her band:

It requires a lot of rehearsal to play the songs. My band always tells me I better change the group’s name from Sonicbloom to Boot Camp!

Similary, life is too complex and chaotic to immediately transfer what you learn in books to everyday situations. For example, you have probably read multiple times about mindfulness, but chances are, in the middle of your work day you may not be mindful. Racing around, traffic, kids, the 101 things you need to do. You are not focused on the suggestions from a book–you are just trying to survive in the modern world. Deliberative practice, including meditation and compassion practice (tonglen), enables us to work with what we learn from books so that it naturally arises without effort in everyday situations. All of a sudden, without thinking, without effort, we have moments of mindfulness.

Hiromi says “Focus, continuous training, and love and passion for what you do, more you practice, more you can fly” and “I wanted to bring what Jackie Chan does in Kung Fu to what I do on piano.” The more you meditate, do compassion training, and other practices the more you can fly in everyday life.

In my next post I will dive into this a bit more.

Don't Know

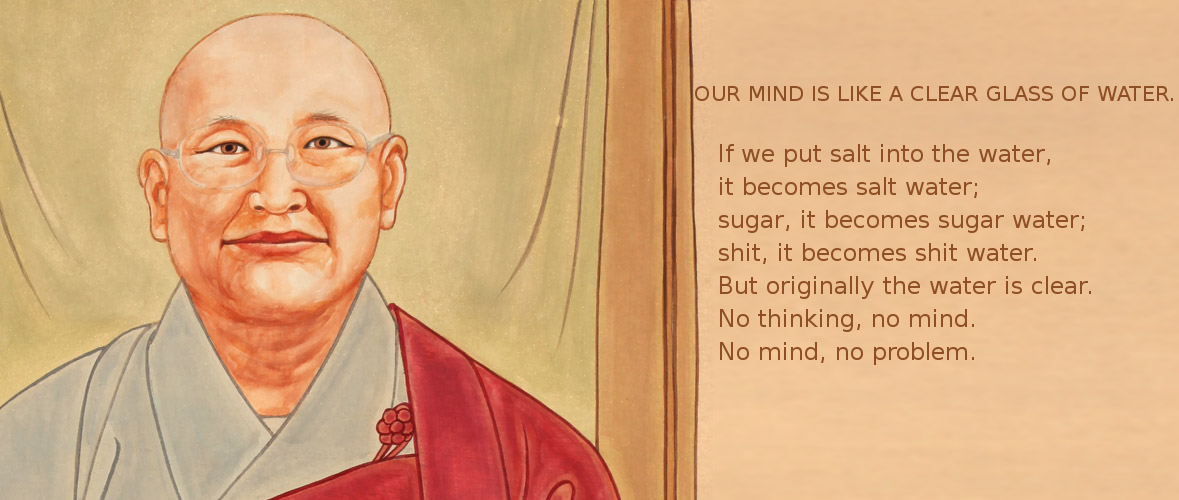

Zen Master Seung Sahn. Art from the website prajna-galleries

Zen Master Seung Sahn. Art from the website prajna-galleries

As many of you know we have been searching for a space to hold our meditation sessions and other events. We sent out a number of emails to area churches and looked at commercial office space to rent. A few times it looked like we found what we were looking for, only to discover some wrinkle that made the space either far less than ideal or unavailable. Last night I heard of the possibility of a fantastic space–better than any we have looked at so far. So the possibility of having a great meditation space may be on the horizon–or maybe not. This morning, while walking my dogs, I realized that this process of looking for a space is similar to the famous Chinese farmer story. For those unfamiliar with it it goes something like this.

Once upon a time there was a Chinese farmer who lost a horse–it ran away. And his neighbors came around that evening and said “That’s too bad! That is most unfortunate!” And he said “maybe.” The next day the horse came back and brought seven wild horses with him. And his neighbors came around that evening and said “Why that is fantastic, isn’t it?” And he said “maybe.” The next day his son was trying to train the wild horses and broke his leg while attempted to ride one. And, of course, the neighbors came around and said “That is awful! That’s too bad!” And the farmer said “maybe.” The following day army officers came around the village conscripting all young men into the military. They rejected the son because of this broken leg. Yet again, the neighbors came around and this time they said “Fantastic news, you must be very happy.” And the farmer said “maybe.”

So is it good news that we found a potentially wonderful meditation space? Maybe

Alan Watts said of the Chinese farmer story:

The This is from his book Eastern Wisdom, Modern Life: Collected Talks 1960-1969 (public library)whole process of nature is an integrated process of immense complexity, and it’s really impossible to tell whether anything that happens in it is good or bad—because you never know what will be the consequence of the misfortune; or, you never know what will be the consequences of good fortune.

I am at a truck stop in west Texas. Someone approaches me as I pump gas, tells me he has no money but he needs to get to Arkansas to stay with his brother. I give him $10. Will the consequences of that act be good or bad? I simply don’t know. Maybe good; maybe bad. We can extend this don’t know mind to everything.

Stephen Batchelor writes Confession of a Buddhist Atheist (public library)of his time in a Zen Monastery in South Korea:

All I do, hour after hour, is ask myself the question What is this? … All I did for ten hours a day for the next three months was ask myself this question. The first two weeks, when my back hurt and my mind swung between febrile daydreamsfebrile daydreams = fever-like daydreams and lethargy, and the last few days, when I strove unsuccessfully not to look forward to the retreat ending, were the hardest. Throughout the long middle period, I experienced an unprecedented contentment.

The point of this exercise, common in Zen, is to

short-circuit the brain’s answer-giving habit and leave you in a state of serene puzzlement. This doubt, or “perplexity” as I preferred to call it, then slowly starts to infuse one’s consciousness as a whole. Rather than struggling with the words of the question, one settles into a mood of quiet focused astonishment, in which one one simply waits and listens in the pregnant silence that follows the fading of words

Zen Master Seung Sahn wrote in a letterThis is from his wonderful book Dropping Ashes on the Buddha: The Teachings of Zen Master Seung Sahn (public library):

You must keep don’t know mind always and everywhere. This is the true practice of Zen.

The Great Way is not difficult

if you don’t make distinctions.

Only throw away likes and dislikes

and everything will be perfectly clear.

So throw away all opinions, all likes and dislikes, and only keep the mind that doesn’t know. This is very important. Don’t know mind is the mind that cuts off all thinking. When all thinking has been cut off, you become empty mind. This is before thinking. Your before thinking mind, my before thinking mind, all people’s before thinking minds are the same. This is your substance. Your substance, my substance, and the substance of the whole universe become one. So the tree, the mountain, the cloud and you become one. Then I ask you: Are the mountain and you the same or different?

The mind that becomes one with the universe is before thinking.

Valentine's Day and the opposite of loneliness

Marina Keegan. Photo from the book The Opposite of Loneliness: Essays and Stories by Marina Keegan. Ms. Keegan died in a car crash just five days after graduating magna cum laude from Yale.

Marina Keegan. Photo from the book The Opposite of Loneliness: Essays and Stories by Marina Keegan. Ms. Keegan died in a car crash just five days after graduating magna cum laude from Yale.

Marina Keegan–a 22 year old–wrote this a few weeks before her college commencement at Yale:

We don’t have a word for the opposite of loneliness, but if we See the complete Opposite of Loneliness essaydid, I could say that’s what I want in life. What I’m grateful and thankful to have found at Yale, and what I’m scared of losing when we wake up tomorrow and leave this place.

It’s not quite love and it’s not quite community; it’s just this feeling that there are people, an abundance of people, who are in this together. Who are on your team. When the check is paid and you stay at the table. When it’s four a.m. and no one goes to bed. That night with the guitar. That night we can’t remember. That time we did, we went, we saw, we laughed, we felt. The hats.

We all, I think, have had similar experiences to hers. The camaraderie of a college experience, of being in the military, of a close-knit group in high school. The feeling that there are people that are in this together. Those are very intense experiences. Imagine what life would be like if we experienced that, every moment of our day. With everyone we meet or see we would have this intense feeling that we are in this together, we are on the same team, with everyone. even people who cut us off in traffic or have an opposing political view.

We would still have sufferings in our life. We might lose our job, have difficulties in a relationship, have sickness, maybe even chronic illness. But we would feel 100% supported and feel that the entire community has our back.

Unfortunately, many of us don’t feel this strong sense of community. Rather we feel loneliness and a sense of separation. Mother Teresa reportedly said: The biggest disease today is not leprosy or tuberculosis but rather the feeling of not belonging Modern society with its emphasis on individualism seems to exasperate this problem by emphasizing the self. In contrast, in Buddhism we work at letting the self fall away and reducing the barriers between ourselves and the rest of the world. Buddhism strives for the opposite of loneliness.

The book we will start discussing next week, Radical Acceptance: Embracing Your Life With the Heart of a Buddha by Tara Brach, presents methods that help us on this path. Please consider joining us for this book study.

Thanksgiving & Gratitude

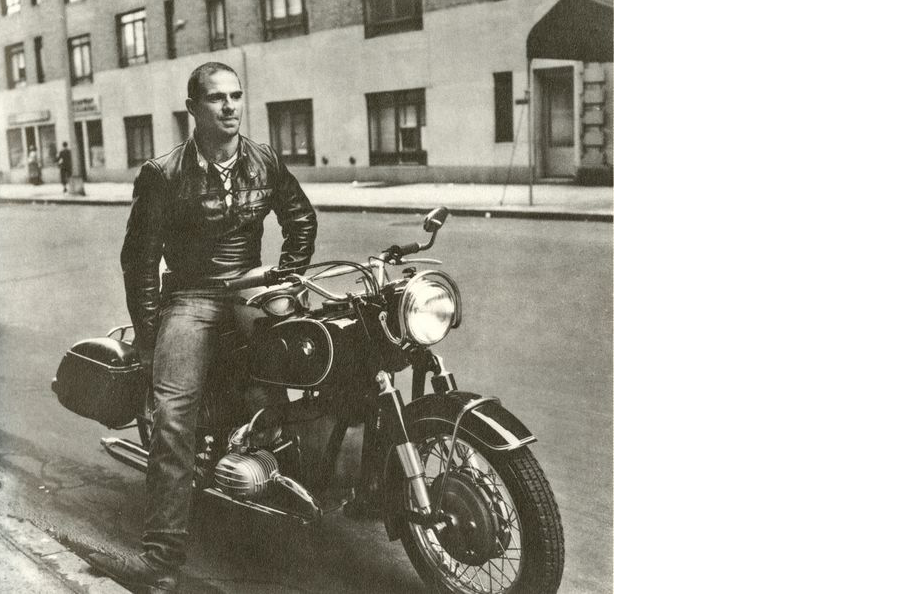

Dr Oliver Sacks. Photo from the book On the Move: A Life by Oliver Sacks.

Dr Oliver Sacks. Photo from the book On the Move: A Life by Oliver Sacks.

I hope everyone has had a wonderful Thanksgiving. As usual Cheryl and I spent our Thanksgiving with my ex-sister-in-law (long story) and her family. Eleven of us around a makeshift table talking, telling stories, laughing. It was fun and relaxing. On the day after Thanksgiving I reflected on giving thanks. There were periods in my life when I did daily gratitude practice. About ten years ago, I would do a chant-like gratitude practice while running. Then there was a period when I would write gratitudes in a journal. More recently, when I would go outside for the first time in the morning, I would look at the sky and give thanks for the new day. For some reason those practices faded.

I thought my life benefited from those practices. A belief supported by research. In a seminal study published in 2003, Dr. Robert A. Emmons and Dr. Michael E. McCullough divided 200 undergraduates into three groups. One group wrote weekly ‘gratitude’ reports. The instructions were:

There are many things in our lives, both large and small, that we might be grateful about. Think back over the past week and write down on the lines below up to five things in your life that you are grateful or thankful for.

Members of one of the other group wrote weekly reports about hassles in their lives (stupid people driving, and doing a favor for friend who didn’t appreciate it ) and members of the final group were asked to write about events in their lives (cleaned out my shoe closet and talked to a doctor about medical school ). After ten weeks the researchers discovered that compared to the other two groups, the gratitude group felt more positive about their lives, exercised more, and were healthier. That is quite an amazing return on just spending a few minutes a week writing down what you are grateful for!

Often our lives are focused on desires. Desires for something we want like some shiny new gizmo for Christmas (I can spend hours and hours researching shiny gizmos on the web). Desires to have something end that we don’t like–like this sprained ankle I seem to have or the world to be less violent. We spend our days focusing on desires. Thinking about the future. Gratitude practice is a good antedote for desires. It helps us focus on the present. It helps us see things clearly.

I’ve previously mentioned Maria Popova and her excellent blog brainpickings. In a review she wrote of the book thxthxthx she writes:

We live in a culture with far, far too much pessimism, cynicism and dystopianism going around. It’s easy to dismiss any inkling of positivity as self-serving Pollyannism, yet there’s plenty of evidence that recognizing our simple blessings greatly increases our well-being. I’m certainly a believer.

The book, thxthxthx, by the way, consists of 200 handwritten thank you notes by Leah Dieterich including:

Perhaps it is time, as Maria Popova suggests, to recognize ‘our simple blessings’. To acknowledge and be grateful for what we have. To be grateful for the life we do have–the good and the bad. Be grateful for, as buddhists say, the 10,000 joys and the 10,000 sorrows of life.

Oliver Sacks, in his book Gratitude writes:

At nearly 80, with a scattering of medical and surgical problems, none disabling, I feel glad to be alive — “I’m glad I’m not dead!” sometimes bursts out of me when the weather is perfect… I am grateful that I have experienced many things — some wonderful, some horrible — and that I have been able to write a dozen books, to receive innumerable letters from friends, colleagues and readers, and to enjoy what Nathaniel Hawthorne called “an intercourse with the world.”

A Discussion on Compassion.

Compassion is the ability to see what needs doing right now and the willingness to do it right now - Brad Warner, Zen Priest.

It is not enough to espouse compassion, you have to act on it to make it real - Dalai Lama.

The whole idea of compassion is based on a keen awareness of the interdependence of all these living beings, which are all part of one another, and all involved in one another - Thomas Merton

We all live busy lives. We work at hard jobs often putting in more than 40 hours per week. Then there are all the other tasks that need doing: laundry, shopping, cooking, taking care of our kids or our parents. We unwind by watching a tv show or by surfing the web. Sometimes it seems that if we can live this modern life and just have a bit of happiness, that would be enough. We may be aware of compassion but don’t take time to consciously fit compassionate acts into our lives.

Just this past week I received email from a friend–a Zen priest who was ordained at the same ceremony I was. He said he was quitting his university job in Oregon and moving to Maryland with his wife and kids to live and work in a Catholic Worker intentional community that serves the homeless. That seems like a life focused on helping others. But what about the rest of us who are struggling with living, not in a monastic intentional community, but in modern urban life? Where does compassion and helping others fit in?

I would like to invite you to a discussion on Sunday 15 November at 2pm at Blackstone Coffee, 1113 Jefferson Davis Hwy (look for a ‘Zen’ sign on our table). The topics are 1) how can we be more compassionate in our daily lives and 2) what can we do as a small community to foster compassion. To seed this discussion, I have a few short videos and a few web links.

This first video (surprisingly, an insurance company advertisement) was discovered by Ted Pickett, one of our community members.

This next one is in a similar vein:

This last video is from an organization envisioned by the Dalai Lama called A Force For Good (There is a variety of information on their website and a short explanation at Daniel Goleman on the Dalai Lama’s Vision for Good)

Bernie Glassman (wikipedia article) authored a number of books about engaged buddhism. He offers three tenets:

Entering the stream of Socially Engaged Spirituality, I vow to live a life of:

Not-knowing, thereby giving up fixed ideas about ourselves and the universe

Bearing witness to the joy and suffering of the world

Doing Action arising from Not Knowing and Bearing Witness

There are some interesting short articles here, including A Day with Bernie Glassman and Bearing Witness- A Harvard Divinity School Talk (this last talk mentions a video about him which I could not find on the web).

If you have other videos or links you think relevant to the discussion please post them to our forum.

I hope to see you at the discussion!

subscribe via RSS