Silence

Image from the book A Graphic Cosmogony, Alex Spiro editor.

About a month ago I had laryngeal surgery and was on strict voice rest for two weeks. This was a new experience. I’ve been on silent retreats but that experience was different. During silent retreats everyone is practicing silence and the environment is very constrained–we meditate, do work practice, study, and eat all in silence at a retreat center. With this experience I was out and about in everyday life. I was teaching my university classes without speaking. I would type out the few things I wanted to say and display them using a projector. If a student asked a question, I would answer in the same way. I was amazed at all the ideas students had when allowed to express themselves without interruption or comment. In one night, I found and read a book on the web, “Stop Talking: Indigenous Ways of Teaching and Learning and Difficult Dialogues in Higher Education.” The authors talk about teaching at an ‘earth-based pace’ and advise:

Image from the book A Graphic Cosmogony, Alex Spiro editor.

About a month ago I had laryngeal surgery and was on strict voice rest for two weeks. This was a new experience. I’ve been on silent retreats but that experience was different. During silent retreats everyone is practicing silence and the environment is very constrained–we meditate, do work practice, study, and eat all in silence at a retreat center. With this experience I was out and about in everyday life. I was teaching my university classes without speaking. I would type out the few things I wanted to say and display them using a projector. If a student asked a question, I would answer in the same way. I was amazed at all the ideas students had when allowed to express themselves without interruption or comment. In one night, I found and read a book on the web, “Stop Talking: Indigenous Ways of Teaching and Learning and Difficult Dialogues in Higher Education.” The authors talk about teaching at an ‘earth-based pace’ and advise:

Stop Talking

Set down your electronic devices. Set down your books and your pens. Go outside if possible; otherwise, find a window. And then for a minute or two, let go of your thoughts and listen to the wind. Pay attention to the land you are standing on and to the living things that share your space. Breathe intentionally from the common air. Notice how you feel. Stay with it as long as possible. Return to it as often as necessary

During my two weeks of silence, when I was out in the woods walking with my wife, Cheryl, and dogs, in addition to listening to the wind, I would listen to Cheryl talk about something that happened at work, or some idea she had and not interrupt her. And listening to her I realized how much I must interrupt her. Initially, I felt frustrated that I couldn’t respond, but with days of practice I grew more comfortable just listening and felt I was really hearing her voice and who she was.

This whole experience made me think about listening and how sometimes–maybe MOST times–people just want to be heard.

When someone says something, they don’t want to be interrupted to hear my, official “What does Ron Zacharski think”, take on what they are saying. For a number of years I was involved in an online Zen book study group. After a person would say something about a life experience, it would be common for someone to offer an opinion or unasked for advice. Perhaps the best response to someone who shares something about their life is quiet acknowledgement.

Gloria Steinem in her book “My Life on the Road” writes:Many of these quotes are from the wonderful website brainpickings.org by Maria Popova, an amazing and talented professional reader.

One of the simplest paths to deep change is for the less powerful to speak as much as they listen, and for the more powerful to listen as much as they speak.

She writes:

When people ask me why I still have hope and energy after all these years, I always say: Because I travel. Taking to the road—by which I mean letting the road take you—changed who I thought I was. The road is messy in the way that real life is messy. It leads us out of denial and into reality, out of theory and into practice, out of caution and into action, out of statistics and into stories—in short, out of our heads and into our hearts

People in the same room understand and empathize with each other in a way that isn’t possible on the page or screen. Gradually, I became the last thing on earth I would ever have imagined: a public speaker and a gatherer of groups. And this brought an even bigger reward: public listening.

She suggests:

Spend some time on the road… in an on-the-road state of mind, not seeking out the familiar but staying open to whatever comes along. It can begin the moment you leave your door.

Like a jazz musician improvising, or a surfer looking for a wave, or a bird riding a current of air, you’ll be rewarded by moments when everything comes together. Listen to the story of strangers meeting in a snowstorm that Judy Collins sings about in “The Blizzard,” or read Alice Walker’s essay “My Father’s Country Is the Poor.” Each starts in a personal place, takes an unpredictable path, and reaches a destination that is both surprising and inevitable — like the road itself.

More reliably than anything else on earth, the road will force you to live in the present.

Be well.

No talking

This creative commons Flickr image is from Nicola Jones.

Last Friday I had some minor laryngeal surgery in Richmond, Virginia. I have some pain. I am on pain meds that make me loopy. The nurse warned my wife that I might be grumpy because of the steroids I am on (and I think I am grumpier). I am off of caffeine, and on a soft food diet (smoothies, scrambled eggs). I am on strict voice rest for what looks like 2 weeks and then partial voice rest for another week. Amid all this I realized something: it is a lot easier to practice Zen when you are feeling well and things are going your way.

This creative commons Flickr image is from Nicola Jones.

Last Friday I had some minor laryngeal surgery in Richmond, Virginia. I have some pain. I am on pain meds that make me loopy. The nurse warned my wife that I might be grumpy because of the steroids I am on (and I think I am grumpier). I am off of caffeine, and on a soft food diet (smoothies, scrambled eggs). I am on strict voice rest for what looks like 2 weeks and then partial voice rest for another week. Amid all this I realized something: it is a lot easier to practice Zen when you are feeling well and things are going your way.

The day after the surgery I meditated and it was like switching channels on some cable network that only plays fantastical shows. There I am on some tall fortress made of cushions surveying some battlefield and I am a bit worried the fort will topple over. Focus on my breath. Cheryl and I are having some argument about whether we are currently in Costco or in bed sleeping. Focus. There’s some Great Dane that jumps on his owner’s motorbike for a ride. Eeeks. I am awake, trying to meditate, and I am having a slideshow of weirdness. And the next day’s meditation is more of the same.

It’s also challenging to practice compassion and generosity. When I am sick I want to be the center of the universe and get a tad grumpy when things don’t go my way. How come Cheryl is going around and around and around the block trying to find a parking place when she should just park so we can go in to Boyer’s Ice Cream and get a nice cold shake for my throat. Doesn’t she know I am sick? A student inititiates a chat in GoogleTalk to get some clarification about a programming assignment and I am irritated.

These are perfect opportunities for practice. Perfect opportunities to touch grumpiness, irritation, racing wild thoughts. To examine them, to accept them (yes, I am grumpy) and let them go. It’s easy to practice compassion in a nicey nicey world, perhaps sitting on your meditation cushion spreading compassion mentally to people who are challenging to to. It’s quite another to engage in compassion as right action when that person is hollering at you, or, in my case, simply engaging in compassion when you are not feeling well.

Last night I read a bit of the Toni Bernhard book How to Wake Up: A Buddhist-Inspired Guide to Navigating Joy and Sorrow where she says that when you catch yourself ruminating on your struggles try an exercise she calls “Start where you are.” Well, these last few days I have been ruminating on my struggles so maybe this exercise is for me. She suggests reflecting on how everyone’s life is sometimes easy and sometimes hard. About an hour after reading this passage, I received a post from my Zen Teacher, Daiho. In it he said that he fell hard that morning on a training run in the desert. He broke four bones in his hand, the doctor splinted the hand and is considering pins and screws. That Zen sandwich of me ruminating on my sorrows, Bernhard saying no one gets a pass on sorrow, and hearing of my teacher’s injury was a good reminder.

No one gets a pass on life’s struggles. Don’t believe me? Listen to some country music. Gary Allen Sings:

Life ain’t always beautiful

Sometimes it’s just plan hard

It was good to reflect on the fact that everyone struggles and then acknowledge my difficulties— my struggles. And think I start with where I am. To at least make an attempt to accept and engage my life as it is.

The task for all of us is to live our lives with this world as it is. It is a practical task. Unless we practice, we will live our lives off-balanced, constantly reacting to what is going on around us. Sickness pushes us one way, …. off balanced and in-chaos. With practice you can live a life filled with poise. Someone or something pushes you and you bobble back to balance. Instead of reacting, you are responsive. Instead of reacting by screaming, shopping, or whatever, you gain an ability to respond and not react and your response is friendliness, compassion, and joy.

Be well.

The Roshi Makes Shitty Coffee

Image by Duncan C. Creative Commons CC-By-NC 2.0

My friend, Bobby Byrd has this brief poem in his book Otherwise, My Life is Ordinary:

Image by Duncan C. Creative Commons CC-By-NC 2.0

My friend, Bobby Byrd has this brief poem in his book Otherwise, My Life is Ordinary:

Koan

The Roshi makes shitty coffee

The Roshi in this poem refers to Rev. Dr. Harvey Daiho Hilbert Roshi and indeed he makes shitty coffee. Bobby, I, and a host of others would be at some weekend meditation retreat lead by Daiho. It’s afternoon, we are dragging a bit and all we would have to drink would be some cheap coffee from a container opened months ago made in an old percolator that Daiho turned on at 5am that morning. Ocassionally Bobby or I would dash to Starbucks to bring coffee back for the people who wanted decent coffee. Of course a real coffee connoisseur wouldn’t dream of drinking Starbucks coffee. That’s not the only time I have had a desire for good coffee. Several times a year I drive 2,000 miles from Virginia to New Mexico and when I need a caffeine fix, I start looking for a Starbucks coffee shop. At home I grind whole beans in a burr grinder and brew the coffee in a hand drip ceramic coffee dripper.

In one of the first teachings of the Buddha he says that desire is the principal cause of dukkha or suffering. This is expressed beautifully in the poem I mentioned in the last post, Hsin Hsin Ming:

The Great Way is not difficult for those who have no preferences. … Make the smallest distinction, however, and heaven and earth are set infinitely apart

How do I reconcile coffee snobbery with this core buddhist belief? Or how do I reconcile any of my preferences–my preference for green enchiladas at Chopes in La Mesa, for Frozen Custard from Caliches in Las Cruces or Dairy Godmother in Alexandria over any other ice cream? As mentioned in the last post, it’s not the preference that will lead to suffering but the attachment to that preference. Say I need a coffee fix in West Texas and I drive for several hundred miles without encountering a Starbucks and now I feel life sucks, this trip is misery, on and on because of no Starbucks. This attachment to a preference is a big problem. On the other hand, if I need a coffee fix in West Texas, look for a Starbucks for a hundred miles and. not finding one, stop at a truck stop and enjoy their brew, my preference for Starbucks is no big deal.

One way of lessening this attachment to preferences is a self-denial practice proposed by the Stoic, Seneca. In this practice you live as if you do not have what you prefer. In the coffee case, the practice would be to drink shitty coffee. I tried this twice in the last year. Once I bought a 10.5 ounce jar of Nescafe Instant Coffee from Walmart, which made something like 150 cups of coffee. For months, that was the only coffee I drank at home. The next experiment was not as bad–again a Walmart trip, this time for a 30 ounce plastic tub of Folgers Ground Coffee. These experiments helped me view good coffee as a perk, as something that was special, and not a requirement for a good day. William Irvine, the author of the worthwhile book A Guide to the Good Life: The Ancient Art of Stoic Joy says that one benefit of this approach is that the person who does this grows confident that doing without Starbucks is no big deal. Doing without going to their favorite restaurant or being cold when outside is no big deal. We learn we can easily live without our preferences. This self-denial is very good practice.

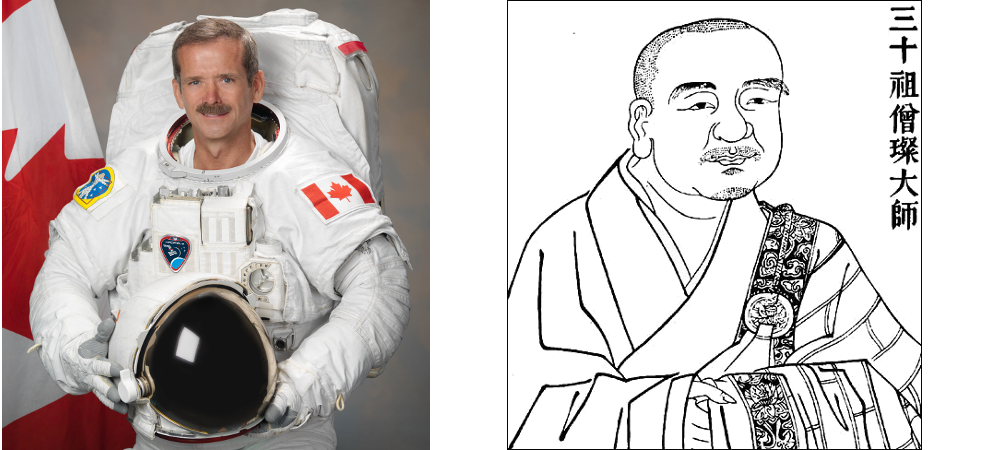

The astronaut and the monk

Both images are in the public domain

Chris Hadfield is a Canadian astronaut and pehaps one of the more famous astronauts due to his YouTube videos on a range of topics and his playing guitarCheck out his epic cover of Space Oddity in space. A few years back I listened to an interview he had with Terry Gross. In it he said:

Both images are in the public domain

Chris Hadfield is a Canadian astronaut and pehaps one of the more famous astronauts due to his YouTube videos on a range of topics and his playing guitarCheck out his epic cover of Space Oddity in space. A few years back I listened to an interview he had with Terry Gross. In it he said:

If the only thing you really enjoyed was whipping around Earth in a spaceship, you’d hate being an astronaut. You can’t view training solely as a stepping stone to something loftier. It’s got to be an end in itself. You train for years. If you viewed training as a dreary chore, not only would you be unhappy every day, but your sense of self-worth and professional purpose would be shattered if you were scrubbed from a mission — or never got one. Because I didn’t hang my happiness on space flight, I was excited to go to work every single day.

He says getting in space depends on many variables and circumstances that are entirely beyond an individual astronaut’s control. So for Hadfield, it always made sense to view space flight “as a bonus, not an entitlement.”” And like any bonus it would be foolhardy to bank on it.

This interview reminded me of a poem, Hsin Hsin Ming, written by Sengcan in 6th century China. It starts:

The Great Way is not difficult for those who have no preferences. When love and hate are both absent everything becomes clear and undisguised. Make the smallest distinction, however, and heaven and earth are set infinitely apart.

I keep coming back to this line again and again. My interpretation is more along the lines of The Great Way is not difficult for those who have no ATTACHMENT to preferences. Of course, we all have preferences–both big and small preferences. Many, many preferences. Maybe we think this current week sucks and this coming weekend looks no better, but the weekend after that, boy oh boy, we plan to head to the mountains, get a room at our favorite hotel, eat at our favorite restaurant. We have it all planned in our minds. But that weekend may not happen as planned. We may end up having to work, or we may get there and find the restaurant is closed for that week, or the town is jammed with a huge loud motorcycle rally. If we were attached to the weekend as planned we could get depressed, angry, you name it. “My weekend is ruined because my favorite restaurant is closed. This whole trip is a bust.” Believe me, I’ve had similar experiences over even trivial things more times than I care to admit. Some of us are unhappy in our day-to-day lives and view happiness as something that will happen when we attain our goals–a better job, an ideal relationship, a degree. Then we will be happy. But attaining any of these is beyond our complete control and even if we attain some of them, the reality of them might not match our expectations. What a bummer, to put it mildly.

Life is more enjoyable, moment by moment, if we are not attached to preferences. If, as Hadfield says, we view our preferences as bonuses and not entitlements. Hadfield says. “Too many variables are out of my control. There’s really just one thing I can control: my attitude during the journey.” Looking back at his life as an astronaut, Hadfield says his job was not about flying around in space: “It was really about making the most of my time here on Earth.” Or to generalize — life isn’t about reaching a set of goals, it is about making the most of our time here on earth.

Hillerman Country

Even before moving to New Mexico, I loved Tony Hillerman novels. There I was on a farm in Northern Wisconsin in January–below zero, snow on the ground– reading Hillerman’s descriptions of Shiprock, Window Rock, Gallup and the terrain and open sky of the Southwest. Now the mystery series has been continued by his daughter, Anne, and I just finished reading her first novel, Spider Woman’s Daughter. One of the main characters is Officer Bernie Manuelito who worries about a mother who is old and frail, a sister who is drinking heavily (and to Bernie’s eyes wasting her life), an uncle who has been shot in the head and in a coma in Santa Fe, and the investigation of that shooting which seems to be going nowhere.

Even before moving to New Mexico, I loved Tony Hillerman novels. There I was on a farm in Northern Wisconsin in January–below zero, snow on the ground– reading Hillerman’s descriptions of Shiprock, Window Rock, Gallup and the terrain and open sky of the Southwest. Now the mystery series has been continued by his daughter, Anne, and I just finished reading her first novel, Spider Woman’s Daughter. One of the main characters is Officer Bernie Manuelito who worries about a mother who is old and frail, a sister who is drinking heavily (and to Bernie’s eyes wasting her life), an uncle who has been shot in the head and in a coma in Santa Fe, and the investigation of that shooting which seems to be going nowhere.

This morning I thought, Good grief, What a life she has! Where is there room for joy and happiness? Then I thought we all have similar lives filled with worry and stress. Worrying about the health of our parents, our own health, the well-being of our children. Stressing over our job, money, our relationships. We have an over-abundance of things to worry and stress about that can keep us occupied 24/7. And this worry acts as a filter to the present moment. We think about our worries instead of clearly seeing what is in front of us. We might be out walking our dog but our minds are regurgitating the latest hassles at work which fill us with a slight anger. We might be sitting with our parents in their living room but our minds are off weaving a story of how frail they look which fills us with worry.

If the Hillerman novel was focused on just recounting the internal worries of Bernie Manuelito it would be a pretty boring read. Instead, Bernie often stops the internal yakking to appreciate where she is. At times she is present in the moment.

Finally, the view she loved, the San Juan River south of the highway, flowing between rows of towering ancient cottonwoods.

The sky was majestic. The Sandia Mountains rose like a rugged blue monolith to the east, glowing in the reflected oranges, vivid reds, and brilliant sunflower hues of the sunset. He put his arm around her as they watched the light change from magenta to smoky rose and dissolve into the soft gray of summer predarkness.

We too can work toward being present in the moment. We can be present with our parents in their living room without some distracting constant dialog in our minds. We can walk the dog and simply be walking our dog. Instead of thinking Good grief, my life is so hard. I work long hours, I’m exhausted when I get home. blah, blah, blah. we can just be present in the moment. That’s where happiness lies. Our lives may indeed be hard. We may work long hours. We may have some illness. But by constantly thinking about all this we are just working ourselves up more and more. More anger, more worry, more suffering. The path out of this is working on being present in the moment. This is the focus of Zen and why we practice meditation.

subscribe via RSS